They Called Us Creek: The Hidden Ancestors of Southeastern Black Americans

What if the people we call “Creek Indians” were reclassified, renamed, and now live on as Black families across the Southeast?

It sounds impossible — until you start digging.

For generations, history books have told us that the Creek Indians were a "Native American tribe" who lived in Alabama and Georgia, fought the U.S. government, and then vanished westward on the Trail of Tears. Meanwhile, Black Americans were said to have arrived later — as enslaved Africans, brought across the Atlantic in chains.

But what if that story isn’t the whole truth?

What if the people known as "Creeks" didn’t disappear at all — but were absorbed, renamed, and legally reclassified in a system designed to erase nations and replace them with races?

What if your grandmother’s stories about “Indian” blood weren’t folklore, but suppressed memory?

What if the people we now call "Black"—particularly those with deep roots in Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida—are the descendants of the very nations once called Creek?

This is the history that was hidden from "Black" Americans in the south during slavery.

The Creek Confederacy Was a Nation, Not a Tribe

Before it was labeled "Creek," the Maskoki or Muscogee Confederacy was one of the most advanced civilizations in the Southeast. According to Albert Gatschet, a 19th-century ethnographer with the U.S. Bureau of Ethnology, the Maskoki were not a single tribe, but a confederation of nations:

"Among the various nationalities of the Gulf territories the Maskoki family of tribes occupied a central and commanding position..." (Gatschet, Migration Legend of the Creek Indians, p. 50)

These nations included the Apalachee, Kawita, Abihka, Kasihta, Yámassi, Hitchiti, and many others. Gatschet classifies them into four distinct branches based on linguistic and geographic origin:

Maskoki Proper: Maskoki-speaking peoples of Coosa, Tallapoosa, and Chattahoochee rivers.

Apalachian Branch: Southeastern peoples like Hitcheti, Apalachee, and Yámassi.

Alibamu Branch: Koassáti and Witumka groups.

Cha’hta (Western) Branch: Chicasa, Pascagoula, and Biloxi in Mississippi.

This wasn’t a "tribe." It was a sacred governmental and ceremonial system spread across what is now the Deep South. Each group held its own dialect, council-house, ceremonial roles, and sacred towns, but all shared a common linguistic and cultural framework.

“Creek” Was Never Their Real Name

The word "Creek" wasn’t a name the people gave themselves. It was a colonial term used by the British to describe American peoples who lived along rivers and creeks.

The true names of these nations were based on town identity — not racial or tribal identity. You were known as a Kasihta citizen, or from Abihka, Kawita, Tuckabatchee, or Eufaula.

Even the term "Muscogee" (or Maskoki) was not originally used by all of the people labeled Creek. Gatschet and other researchers suggest it may have come from foreign influences, and some Creek leaders, like Malatchi of Kawita, never used it at all. He referred to Apalachee, Palachicola, or Kawita — never Muscogee.

Some of these towns still exist in both memory and geography: Tuckabatchee, which gave rise to the Montgomery metro area in Alabama, and Kawita, whose legacy spans across Columbus, Georgia, Phenix City, Alabama, and even Macon, Georgia. These were not small villages but major centers of governance and ceremony. Their names and memory persist today in many local place names where Black Southern families reside or originate.

A Dark and Complexioned People

Eyewitnesses from the 1700s and 1800s consistently described the people of the Southeast as dark-skinned, with "cinnamon" or "olive" complexions.

"The complexion of both [Creek and Chahta] is a rather dark cinnamon, with the southern olive tinge." — Gatschet, p. 51

"Among the Maskoki, prognathism is not frequent among them, and the complexion of both is a rather dark cinnamon..." (p. 51)

These weren’t imagined traits — they were documented realities. The Maskoki were described as tall, gifted, eloquent, and passionate. Their customs included sun-worship, matrilineal lineage, totemic clans, and ceremonial red/white color governance.

This aligns closely with many Black American families in the Southeast today, whose roots are called "African" only because the system redefined them to fit the slave economy.

What Happened to Them?

The Maskoki Confederacy did not fall overnight. It was dismantled in waves:

First, through colonial warfare and land seizure.

Then through treaties, removals, and division.

Finally, through reclassification under U.S. law.

By the 1800s, many original Americans who resisted removal were labeled as freedmen or folded into the expanding racial category of "Black."

This process wasn't accidental. It was the legal machinery of empire — designed to erase land claims, destroy sovereign memory, and consolidate power under racial categories.

"These Indians... have become so largely mixed with half-castes in the nineteenth century, that a division on racial grounds has become almost impossible." — Gatschet, p. 52

Many who stayed behind were listed in censuses as "free persons of color" or "Negro," even though their towns, laws, languages, and families were still rooted in "Creek" society.

"Their dialects belong to one linguistic family... and the grammar has repelled every foreign intrusion." (p. 52–53)

They Didn't Disappear — They Were Renamed

The so-called "Creek" Nation didn't vanish. It lives on in "Black" families across the South. These weren't Africans "brought here" in every case. Many were already here — as free people, diplomats, and members of a complex town-based civilization that predated the U.S. by thousands of years.

They were later rewritten as slaves, because slaves had no land. No rights. No memory.

But memory is rising again.

We were never just from the South. We are the South.

We are the descendants of a hidden nation. A reclassified people. A fire that never went out.

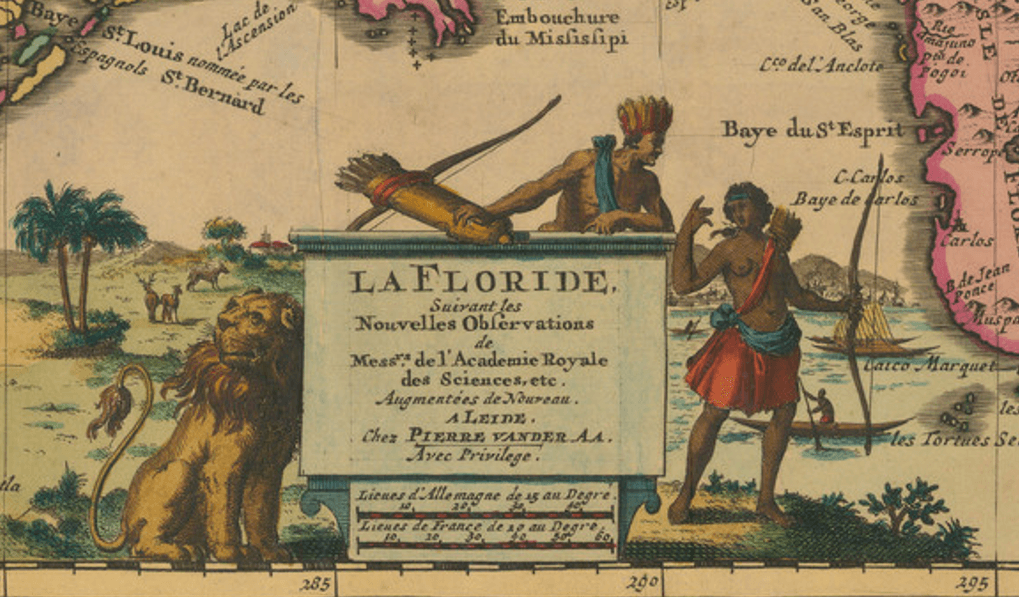

Figure 1. Detail from the 1710 French map “La Floride suivant les Nouvelles Observations.”

This early 18th-century French map depicts the American Southeast as a land of regal, dark-skinned inhabitants—complete with bows, quivers, and ceremonial headdress. A lion rests beside them, symbolizing nobility and strength. The image reflects how Europeans at the time still recognized the sovereign, complex civilizations of the region. Maps like this one captured more than geography—they preserved visual memory of the people we now call “Black” as the original Americans.

Learn More

This story is part of a growing movement to recover the true identity of Southeastern Black Americans. Read more in the upcoming book: Southern Roots: Rediscovering the Nations, Tribes, and True History of Southeastern Black Americans.

Join us at WeAreSouthernRoots.com to reclaim what was stolen, and remember what was never truly lost.

Let us know what you think in the comments!