Descriptions of the Original Americans of the Southeast

What if the people called “Black Americans” today were actually the first Americans?

Not brought here—but already here. Not slaves from Africa—but Indigenous to this land. This isn’t a theory. It’s what early explorers, traders, and historians wrote down when they described the people they encountered in the American South.

And the picture they painted looks nothing like the story we’ve been told.

They Saw Us

James Adair, a British trader who lived among the Chickasaw, Choctaw, and other Southeastern nations for over forty years, gave some of the earliest and clearest descriptions:

“The parching winds, and hot sun-beams, beating upon their naked bodies, in their various gradations of life, necessarily tarnish their skins with the tawny red colour.”

— Adair, History of the American Indians, p. 3

“As the American Indians are of a reddish or copper colour,—so in general they are strong, well proportioned in body and limbs, surprisingly active and nimble, and hardy in their own way of living.”

— Adair, p. 4

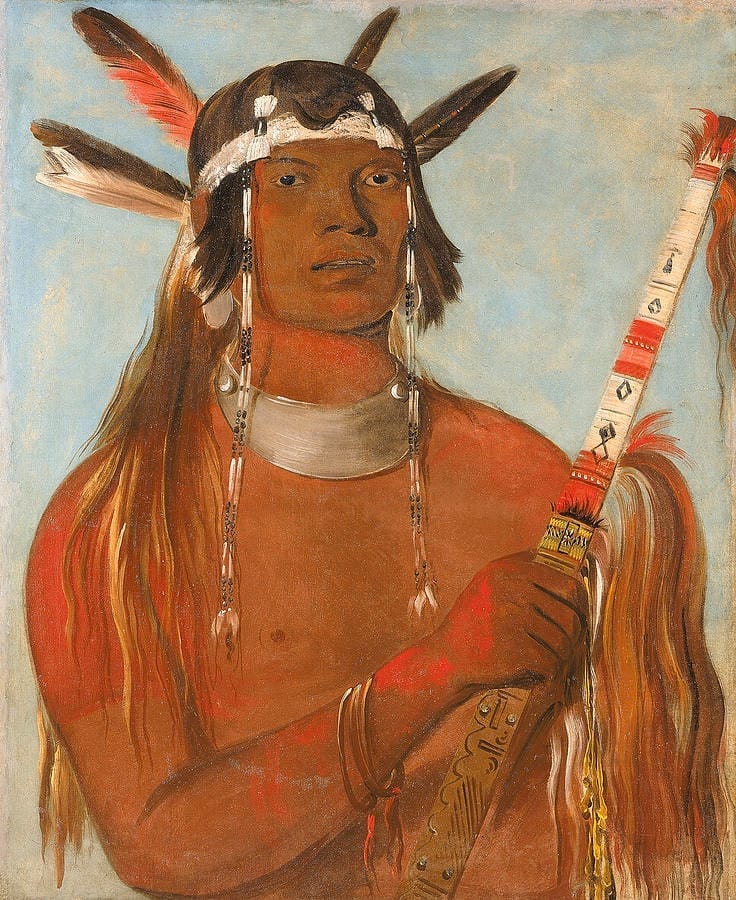

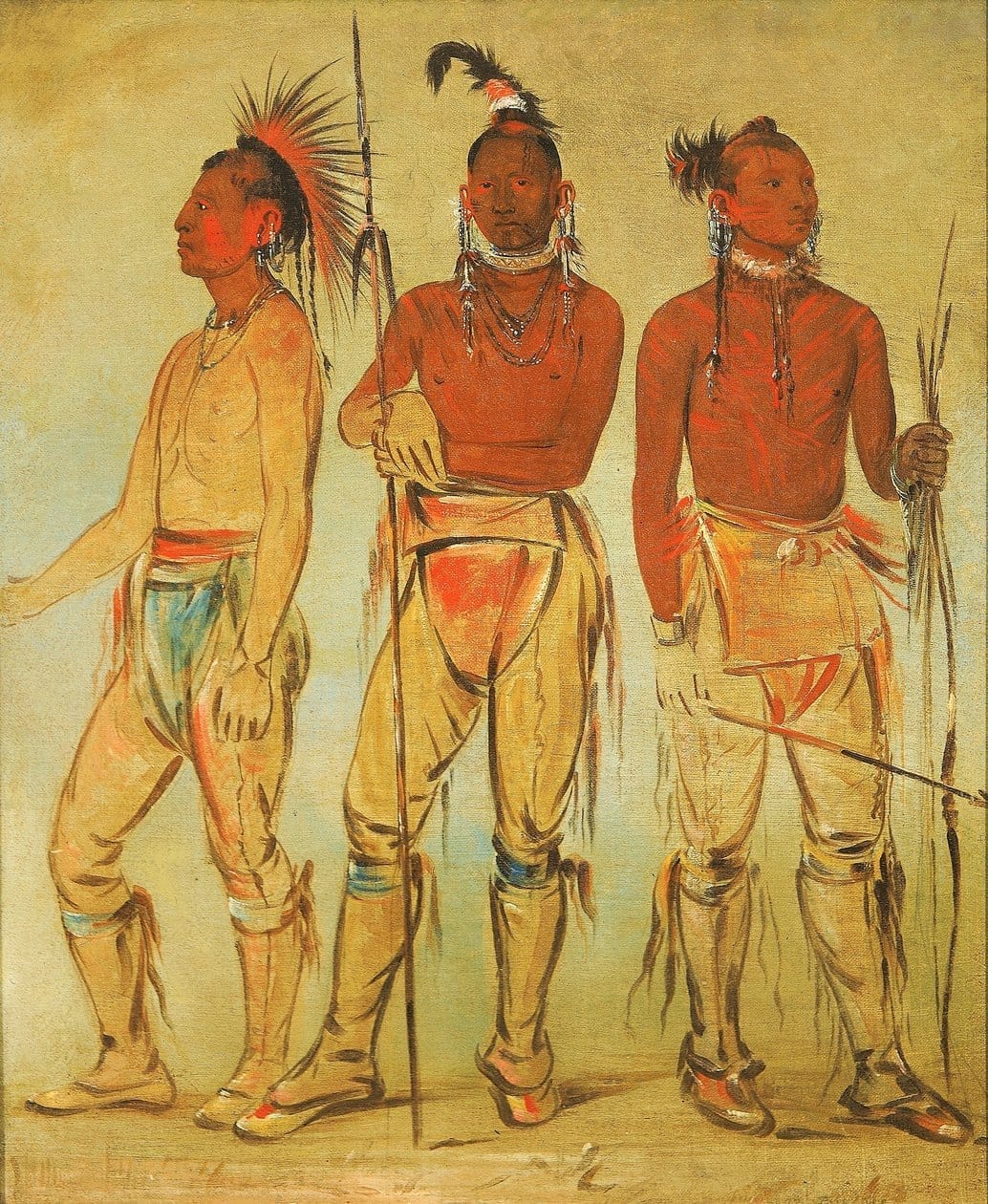

Figure 1. Seehk-hée-da (Mouse-Colored Feather) by George Catlin, 1832

This portrait depicts a Mandan man—painted during George Catlin’s travels among Native nations of the early 19th century. Seehk-hée-da’s copper complexion, strong features, and adorned pipe reflect the warrior-diplomat archetype common to many Indigenous societies of the Southeast and beyond. Though Mandan, his image closely resembles the eyewitness descriptions of Southeastern peoples recorded in the 1700s—people who would later be reclassified as “Black” in the American South.

Collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Adair emphasized that their complexion made sense for their environment—Southern heat, sun, and soil. And today, these same tones are seen throughout the “Black” population of the Southeast.

Other early historians described a similar range of complexions:

“In the territory once occupied by their tribes no topographic name appears to point to an earlier and alien population... the peculiar olive admixture to their cinnamon complexion is a characteristic they have in common with all other southern tribes.”

— Gatschet, A Migration Legend of the Creek Indians, p. 10

Alexander Hewat wrote of Southeastern people:

“Of a brown complexion… their bodies shining with bear’s fat… their stature and bearing often surpassed what Europeans expected.”

— Hewat, Historical Account of South Carolina and Georgia, p. 68

William Bartram, a naturalist who traveled throughout the South in the 1700s, recorded striking details:

“Their complexion, of a reddish brown or copper colour; their hair long, lank, coarse, and black as a raven, and reflecting the like lustre at different exposures to the light.”

— Bartram, Travels, p. 481

He also gave one of the most vivid early descriptions of Southeastern women:

“Women, though remarkably short of stature, are well formed; their visage round, features regular and beautiful; the brow high and arched; the eye large, black and languishing, expressive of modesty, diffidence, and bashfulness. These charms are their defensive and offensive weapons, and they know very well how to play them off. Under cover of their alluring graces is concealed the most subtle artifice. They are, however, loving and affectionate. They are, I believe, the smallest race of women yet known—seldom above five feet high, and I believe the greater number never arrive to that stature. Their hands and feet not larger than those of Europeans of nine or ten years of age…”

— Bartram, Travels, p. 482

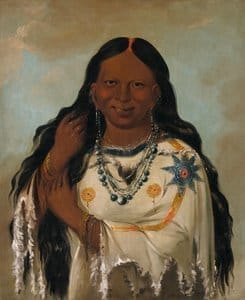

Figure: Kay-a-gís-gis, a Young Woman by George Catlin, 1832

This portrait captures a young Indigenous woman painted by George Catlin during his travels in 1832. Her smooth copper-brown skin, long black hair, and gentle features mirror the descriptions of Southeastern women given by Bartram and others: round face, delicate form, and expressive eyes. Though Catlin identified her as a member of a Western tribe, her appearance reflects a broader pattern—one that connects directly to the women now known as Black Americans in the South.

Collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

He described the men:

“Tall, erect, and moderately robust... their limbs well shaped, forming a perfect human figure; their features regular, and countenance open, dignified and placid... many of them above six feet, and few under five feet eight or ten inches.”

— Bartram, Travels, p. 481–482

A French observer also noted:

“Fine, athletic men… bronze bodies oddly painted… their faces not unpleasant to look upon…”

— Mann, Story of the Huguenots, p. 129

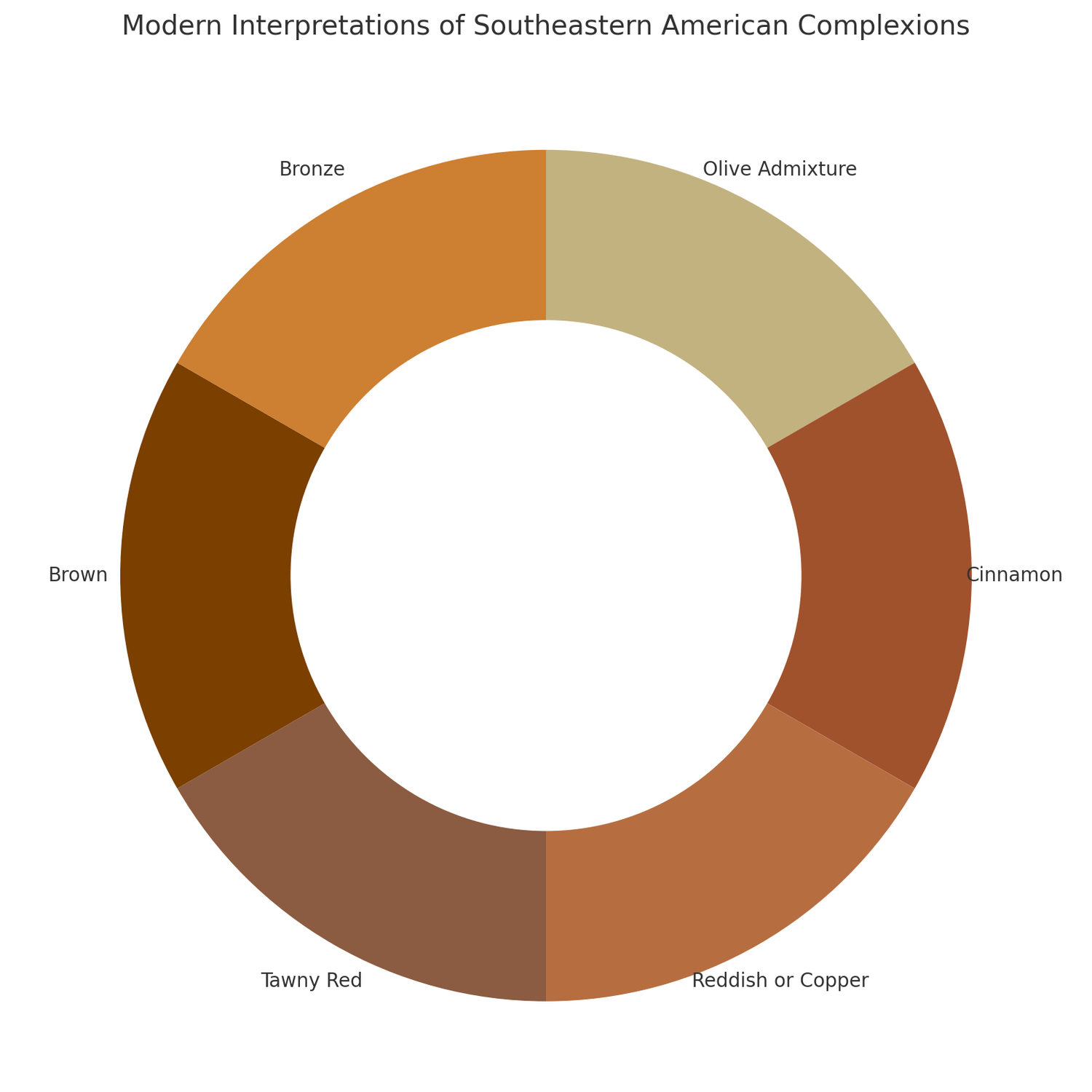

The Complexions They Described

From multiple sources, the complexion of Southeastern Americans was recorded as:

Olive admixture

Cinnamon

Reddish or Copper

Tawny Red

Brown

Bronze

These are the same complexions found among “Black” families in the Southeast today—often within a single household.

These historic descriptions weren’t poetic exaggerations—they reflect real skin tones still seen today in the American South.

Below is a color wheel that further explains:

So, What Happened?

If early observers clearly described a copper-colored, strong-featured, self-governing people—what changed?

The answer is simple: reclassification.

Over time, colonists began erasing the line between “Indian” and “Negro.” Some of this came through intermarriage, but much of it was intentional policy.

U.S. Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins admitted that it was often hard to distinguish between Indians and Negroes in Georgia and Alabama.

That confusion wasn’t accidental—it became the legal and cultural foundation for erasing the identity of people within the United States of America. Once the land was taken and the national names stripped, the people were renamed too.

An original American became an Indian on paper after contact with foreigners from Europe during the Age of Exploration. An Indian became a Negro the moment his nationhood was lost.

The Truth Was Never Lost—Only Hidden

The people known today as “Black” are not outsiders to this land. Many are the direct descendants of the original Americans—described in detail by those who saw them with their own eyes. Copper skin. Tall stature. Strong features. Noble bearing. From the red soil of Georgia to the black earth of the Mississippi—they were here. We were here.

Early explorers described the original Southeastern Americans as copper-skinned, coarse-haired people—strong in both physique and spirit. The same as the “Black” Americans of today. Southern Roots tells their story.

Learn the truth they tried to erase.

Explore the full story in Southern Roots: Rediscovering the Nations, Tribes, and True History of Southeastern Black Americans.

Quote from Southern Roots: Rediscovering the Nations, Tribes, and True History of Southeastern Black Americans.

"The original Southeastern Americans were a tall, copper-toned, spiritually disciplined peoples whose law, ceremony, and architecture reflected a deep-rooted Moorish civilization. - pg. 21

Discover the full story in Southern Roots: Rediscovering the Nations, Tribes, and True History of Southeastern Black Americans.

Let us know what you think in the comments!