Holiwahali, Hilibi, and Wakokai: Sacred Seeds of New Towns

This article is part of our series "The Hidden Nations of the American South," revealing the true town-nations behind today’s Southeastern Black Americans.

In the ceremonial world of the Southeast, founding a new town was not simply a matter of moving to new land—it was a sacred act. Towns like Holiwahali, Hilibi, and Wakokai embody this truth. Each emerged from an older settlement, carrying with it the fire, law, and memory of its parent town while establishing its own identity.

Holiwahali: Dividing the War

Holiwahali’s name is often interpreted as “to share out or divide war” (holi = war, awâhali = to divide). This suggests a ceremonial role within the Confederacy’s red (war) towns. Swanton records that Holiwahali, Atasi, and Kealedji were branches of Tukabahchee, though some traditions claim Holiwahali was older—possibly connected to towns noted in De Soto’s 1500s expedition.

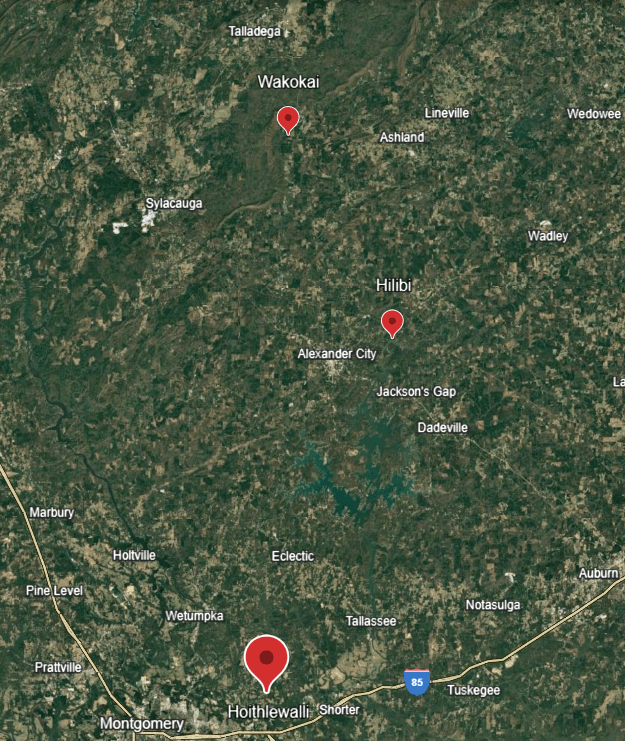

The town’s historic territory lay near Autoshatchee, downstream from Atasi on the right bank of the Tallapoosa River.

Landmarks in the area included Kebihatchee Creek (Cubahatchee), Ofuski (Line Creek), and the mound-rich region known as Húli-Wa’hli—distinguished by fertile red cliffs and cypress ponds.

Holiwahali was fortified and ceremonial, reflecting the defensive and spiritual duties of a red town.

Hilibi: Born in a Moment

Hilibi’s origin story speaks to the quick formation of a new community. According to oral tradition, Hilibi was founded after a dispute in a stickball game. A leader, frustrated by defeat, gathered supporters from Tukabahchee and neighboring settlements. Crossing over a creek, they established a new town—naming it Hilibi (hiliki = quickly) to commemorate the speed of their founding.

Hilibi rose to prominence as a powerful Upper Town, appearing in records as early as 1832. A later branch, Kitcopotaki(“old rotten mortar”), hints at ceremonial ties to food preparation or mound-building traditions.

Historic Hilibi has been linked to the area around Stearns Creek and Tallassee, with possible extensions into present-day Montgomery County, Alabama. Spanish accounts may have referred to it as Hilapi, another derivation of Hilibi.

Wakokai: The Mother Town

Wakokai was remembered as a “mother town,” giving rise to at least two daughter settlements:

Wogufki (“muddy stream”)

Tukpafka

One Hilibi informant told Swanton that Wogufki’s people separated from Wakokai by crossing a creek on a log—a symbolic passage into a new identity. While some traditions say Wakokai was a branch of Eufaula, others insist it separated long before, maintaining its own sovereignty.

A Pattern of Kinship and Separation

These three towns—Holiwahali, Hilibi, and Wakokai—show a recurring pattern in Southeastern town-building: separation through both necessity and diplomacy. Whether due to disputes, population growth, or ceremonial needs, new towns carried forward the spiritual lineage of their origins.

In this way, the Southeastern world was never static. It grew and adapted, each Italua (town) a seed from an older plant, rooted in the same soil of memory and law.

📚 This is part of the Southern Roots blog series revealing the true nations behind modern Southeastern identity.

👉 Explore the full history in Southern Roots: Rediscovering the Nations, Tribes, and True History of Southeastern Black Americans.

Let us know what you think in the comments!